|

Many years ago, while researching London clockmakers I came across a report in the London Gazette for 31st May 1729 which stated that William Moraley, watchmaker of Newcastle had been declared bankrupt and was in prison. This told me very little about the man but an article in the journal of the Northumberland and Durham Family History Society (NDFHS) for Winter 1988 by a Mr. Vaughan, described a pamphlet written by a William Moraley of Newcastle published in 1743 about his unfortunate life. Mr. Vaughan had been related to the Moraleys so had researched the family history which he reported in NDFHS journal for Winter 1990. I was able to access an original copy of the pamphlet in the Newcastle Central Library. Apparently, William Moraley was a descendant of Edward III of England through the female line and was the grandson of Ridley Moraley yeoman of Latterford, Simonburn, Nd., who had died in 1683. Ridley Moraley had three sons Alexander, John and William. William the youngest son, born about 1666, had been apprenticed in the Clockmakers’ Company in London through Henry Child to Philip Corderoy, clockmaker of St Mary Abchurch Parish, for 7 years on 8th February 1680/1 and had later been turned over to Thomas Tompion on 3rd October 1687 and freed by the Company in December 1688. Moraley must have continued to work for Tompion after he was freed. When William Moraley married Martha daughter of John Mason, citizen and Founder, by special licence on 24th November 1697, he stated that he was 28 years old, in the presence of Solomon Bouquet, clockmaker. This was not his true age because he would have been at least 31 years. His bride must have been much younger than William. John Mason, son of John of Wallbree, Wiltshire, had been apprenticed to Thomas Kimberley in the Founders’ Company on 29th September 1650 and freed about 1660. He bound 6 apprentices between 1664-1704 and must have died in January 1710/11 when his last apprentice was turned over to another master on 15 January 1710/11. William Moraley, junior was born in late 1698 and baptised on 1st March 1698/9 at Christchurch Newgate Parish where the family were living. It has been said that William senior continued to work as a journeyman to Thomas Tompion even after his marriage but perhaps he continued to supply the Tompion workshop with watches after his marriage. By the time William junior was old enough to be apprenticed William senior had amassed a small fortune. He had invested £800 (equivalent to about £200,000 today) in the South Sea Company. At the age of 15 in 1714, William junior was apprenticed as a clerk to an eminent attorney in the Lord Mayor’s Court where he continued for two years but as he admits he wasted his time wandering around the streets and got into bad company, so his father took him into his own workshop to teach him watch and clockmaking and promising to advance his son’s fortune when the right time came. William Moraley, junior was apprenticed in the C.C. to his father on 5th May 1718 and would have been able to take his freedom of the company by patrimony at the age of 21 years ( because his father was a freeman) but he never did take his freedom and consequently never worked as a master watchmaker.

The leading watch and clockmaker in Newcastle from 1680-1723, was Deodatus Threlkeld, who had a very profitable business over that period. His former master, Abraham Fromanteel had retired to Newcastle about 1712 and worked as a clockmaker with his journeyman, Benjamin Brown, until Abraham died in 1731. On 27th July 1723 the following advertisement appeared in the Newcastle Courant :- “Deodatus Threlkeld being gone from Newcastle to reside at his house at Tritlington, near Morpeth, will continue to make and sell as many gold and silver watches as he, with his own hand can finish, at which place may be furnished with the same, and also at Mr. Francis Batty’s, goldsmith at Newcastle, or at Thomas Shipley’s, merchant in Morpeth, at all which places watches will be taken in and mended. The said Deodatus Threlkeld will be at Morpeth every Wednesday, and to be heard of at the said Mr. Shipley’s.” Threlkeld indicates here that he was a watch finisher as well as a retailer. From the earliest English watches made at the beginning of 17th century a number of craftsmen had made the different parts of the watch and the watch finisher assembled these different parts such that the watchmaker only had to adjust and regulate the watch before he sold it to the customer. It is often possible to see the same design of parts in the watches of different watchmakers. For example, similarly pierced, balance cocks were used by Samuel Watson, Thomas Tompion, George Graham and William Moraley. (see the Camerer Cuss Book of Antique Watches). William Moraley’s brother in the Bigg Market, Newcastle must have seen the above advertisement and sent the information to his brother in London because in the same newspaper, less than a month later, on 24th August 1723 we read of William’s arrival in Newcastle :- “ William Moraley, Clock and Watchmaker, who served his Time with, and wrought for the famous Mr. Tompion at London, till his Decease, is lately come into his Native Country and designed to reside in Newcastle upon Tine, who makes and sells Gold and Silver- Watches, mends and cleans all Sorts of Clocks or Watches; and is to be met with at John Morley’s House, next Door to the Black and Grey, in the Big- market, Newcastle.” We note that William worked for Tompion until the latter’s death, but there is no mention of working for the famous George Graham after Mr. Tompion. According to William junior’s narrative his father’s business went well for two years until William senior heard of his brother, Alexander’s death, in London in 1725. William senior went to take possession of his brother’s effects but died himself at Harwich on his return journey. From that time William junior said his problems started because his father had made a will leaving only his working tools and twenty shillings to his son and the rest of his estate to his widow Martha. We do not know what happened to the business after William senior’s death but William junior did not continue it. William junior remained with his mother until her remarriage to Charles Isaacson on 19th October 1728 at St Andrew’s Church, Newcastle. William then tried always to get money from his mother and in the end decided to go to London to find his fortune. She had given him 12s but that did not last long when he arrived in London. He borrowed money from anyone who would lone him money until at last his creditors grew tied of him and took him to court and he ended up in prison. He was not able to find work in London, so that he could not have worked in his own name or for George Graham as some people have suggested. William was released from prison in 1729 and while reclining in a public house a gentleman advised him to sell himself into voluntary bondage in exchange for a passage to Philadelphia which he agreed to bind himself for 5 years. He was taken aboard the Bonetta where there were 20 other men who were in similar circumstances to himself. The ship sailed on 7th September 1729 and after many hardships at sea the ship arrived in the Delaware River and docked at Philadelphia on 26th December 1729. William recounts how he and his fellow ‘slaves’ were allowed to visit the Town. He sold his red coat for a quart of Rum and his ‘Tye Wig’ for six pence, with which he bought a three-penny loaf and a quart of cider. William watched while all his companions were sold one by one, before it was his turn, when he was sold for £11 to Isaac Pearson, a smith, clockmaker and goldsmith who lived at Burlington, New Jersey. “He was a Quaker, but a Wet one”. He goes on to say that there were three watchmaker’s shops in Philadelphia; Peter Stretch, the most eminent, John Wood and Edmund Lewis, from London. William worked as a watch and clock repairer, as well as a blacksmith for his master. He was sent out into the country to repair the clocks and watches, which he enjoyed but he soon wanted to return to his old ways and asked his master to turn him over to another master, in Philadelphia. This demand made his master very angry, so William attempted to escape and ran away. He was soon caught and put in prison but was soon released and brought before the Mayor of Philadelphia, together with his master. He agreed to go back with his master, who agreed to reduce his term to three years. His master then became more generous and treated him well. Isaac Pearson had a share in an ironworks to which he sent William to work. Sometimes William worked as a blacksmith and sometimes he was in the water and sometimes he was a cow hunter in the woods and sometimes he got drunk with joy that his work was ended. At last his iron work was finished and his term of his servitude was over. His master released him and he went to Philadelphia to find a new job. He worked for the watchmaker, Edmund Lewis for a while but the two were of similar temperament and fell out, so William left him and went to work for William Graham, a watchmaker newly arrived from London who was the nephew of the famous George Graham of Fleet Street. He worked for him for 10 weeks at 10 shillings per week wages with board and lodgings. William Graham then wanted to go on to Antigua (in 1733) so Moraley left him. After a number of adventures as well as trying to work as a tinker, William returned to Philadelphia to work as a journeyman for Peter Bishop, a blacksmith, for eight shillings a week and board. He worked at the great hammer, making horse-shoes, horse-shoe nails, rounding of ship bolts and sharpening coulters for farmer’s ploughs. After six weeks his creditors caught up with him and threatened to take him before the magistrate. This forced him to leave Philadelphia and go to New York to avoid his pursuers. Having no success at finding a passage on a ship he returned to Philadelphia and went straight to Burlington where he found a ship bound for England and was taken on as the cook. On the 26th July 1733 they sailed down the Delaware river passing Chester the next day. It took them 13 weeks to sail to Ireland and William managed to find a ship travelling to Workington. William was at last back on English soil arriving back on the 26th December 1733. He had to walk back about 80 miles across the country from west to east in the worst of winter weather, begging for food and shelter on the way. It took him nine days before he reached Newcastle, where he received a warm welcome from his uncle. He stayed three weeks with his uncle in the Bigg Market before going to live with his mother until she died about 1738. His mother’s will indicated that she had left her estate in trust to William but he was only paid a small amount each year, by the executors, to live on. William lived until January 1762 and was buried in St Nicholas churchyard on 19th January 1762. He believed to the end that he had been badly treated by his parents and life in general. If you enjoyed this story, you might enjoy other stories about Early clock & watchmakers of London, the North East and other parts of England. You can find these in my two books: Early Clock and watchmakers of the Blacksmiths' Company Clockmakers of Northumberland & Durham

5 Comments

Rory Tapner

5/25/2022 04:02:10 pm

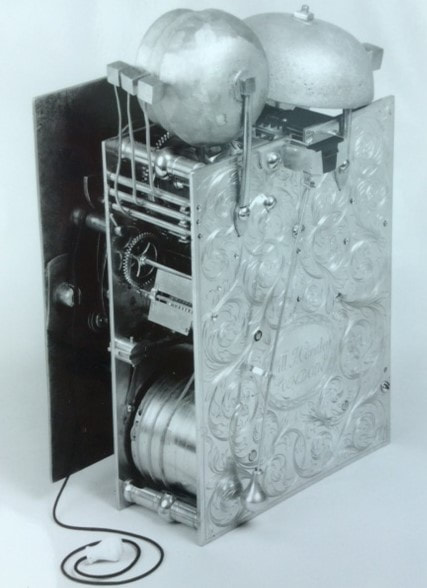

Interesting article. Funnily enough I do have another clock signed Wm Moraley … table clock similar to the one shown in this article, and demonstrating some of the fine engraving one might associate with a clockmaker of much greater repute. If you want a photograph, let me know.

Reply

5/26/2022 02:09:55 pm

Hello Rory,

Reply

keith bates

5/26/2022 09:03:29 am

Hello Rory,

Reply

Ben

11/24/2022 02:12:03 am

I have a long case grandfather clock signed by W M Moraley. I have been researching the clock however have not had much luck finding much out about it.

Reply

11/24/2022 03:29:24 pm

Hello Ben,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorKeith Bates is an amateur horologist who has been researching clocks, watches and chronometers and their makers for over 30 years. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed