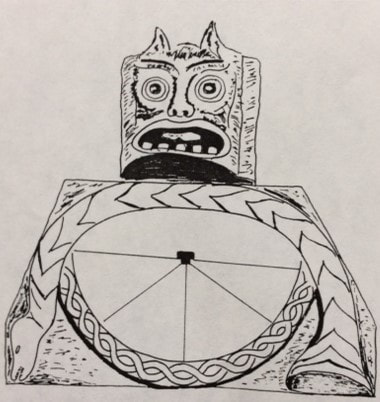

The Rothbury Sundials - Article in Clocks Magazine of November 1991.

By Keith Bates

NOW available for online purchase.

" I’m very pleased with your book, especially the photos ( the clock on the cover is one of my favourites!!)"

Neil – Southampton

Neil – Southampton

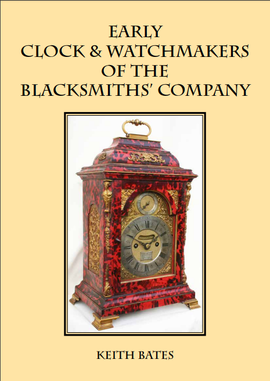

Early Clock and Watchmakers of the Blacksmiths' CompanyKeith's years of research into the Blacksmiths' Company have uncovered the history of many clock and watchmakers. Contains over 400 illustrations and a directory of over 1,500 clock and watchmakers...many previously unknown.

Early Clock and Watchmakers of the Blacksmiths’ Company Now available for purchase for £79 plus FREE P&P (UK delivery) or £30 P&P (EU & USA delivery) |

"Your wonderful book arrived today in beautiful condition."

Travis – New York

Travis – New York

|

|

|

"I have been away and recently returned to find your quite magnificent book. Many congratulations of a fine and fascinating work. It will be of much interest here – particularly the William Clement research. The whole book is beautifully presented."

Lesley – London

Lesley – London