Early longcases from the North East - The works of Abraham Fromanteel 1669 - 1680.

By Keith Bates

Article in Clocks Magazine of October 1990.

The introduction of the pendulum into clocks about 1657 had a pronounced effect on clockmaking in England. Not only were the new clocks more accurate and reliable but they could be made to run for longer periods without winding, and were housed in cases which were elegant pieces of furniture and as such had a much wider appeal.

In his book “Country Clocks and Their London Origins” Brian Loomes relates the history of the Fromanteel family of clockmakers and how Ahasuerus Fromanteel, the head of the family, was first to offer the new pendulum clocks for sale in England.

Ahasuerus had three surviving sons who became clockmakers, all of whom were apprenticed to their father: John who worked independently in London; Ahasuerus junior who worked for his father in London and subsequently in Holland; and Abraham who was apprenticed in 1662. Son, Daniel who was apprenticed in 1663, appears to have died about 1665. Abraham did not apply for his freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company until 1680. The intervening years were rather eventful ones.

In his book “Country Clocks and Their London Origins” Brian Loomes relates the history of the Fromanteel family of clockmakers and how Ahasuerus Fromanteel, the head of the family, was first to offer the new pendulum clocks for sale in England.

Ahasuerus had three surviving sons who became clockmakers, all of whom were apprenticed to their father: John who worked independently in London; Ahasuerus junior who worked for his father in London and subsequently in Holland; and Abraham who was apprenticed in 1662. Son, Daniel who was apprenticed in 1663, appears to have died about 1665. Abraham did not apply for his freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company until 1680. The intervening years were rather eventful ones.

Loomes tells us how the family left London very hastily in 1665 when the plague was at its height. They moved to Colchester but were forced to leave there in 1665 when the plague overtook them there. However they were back in London in June 1666. Three months later in September 1666 the Fire of London, which devastated the city, destroyed one of the Fromanteel workshops in Lothbury. However Ahasuerus did have a workshop at his home in Southwark which was not affected by the fire, so no doubt he was able to take advantage of the situation to further his business.

England’s war with France and Holland 1664-1668, did not help the situation and in particular it must have severely restricted the Fromanteel business in The Hague. So it is not surprising when we hear that Ahasuerus was in Holland as soon as peace was declared.

E G Aghib and J G Leopold in their article “More about the Elusive Fromanteel” in Antiquarian Horology September 1974, state that in July 1668 both Ahasuerus senior and Abraham were in the Hague where Ahaseurus signed a Power of Attorney over to his daughter living in London, while Abraham was one of the witnesses.

Abraham would have completed his apprenticeship in 1669, but he did not apply for his freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company until 1680. Therefore we can assume that he was not working in London during that period, so what was he doing between 1669 and 1680? The answer, in short, is that he was working in Newcastle upon Tyne.

England’s war with France and Holland 1664-1668, did not help the situation and in particular it must have severely restricted the Fromanteel business in The Hague. So it is not surprising when we hear that Ahasuerus was in Holland as soon as peace was declared.

E G Aghib and J G Leopold in their article “More about the Elusive Fromanteel” in Antiquarian Horology September 1974, state that in July 1668 both Ahasuerus senior and Abraham were in the Hague where Ahaseurus signed a Power of Attorney over to his daughter living in London, while Abraham was one of the witnesses.

Abraham would have completed his apprenticeship in 1669, but he did not apply for his freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company until 1680. Therefore we can assume that he was not working in London during that period, so what was he doing between 1669 and 1680? The answer, in short, is that he was working in Newcastle upon Tyne.

The Old Exchange, Newcastle with its turret clock made in 1586 by John Harvie, one of the first clockmakers in Newcastle.

The Old Exchange, Newcastle with its turret clock made in 1586 by John Harvie, one of the first clockmakers in Newcastle.

Abraham probably came directly to Newcastle from Holland in 1669. We do not know why he chose Newcastle as his business centre but we do know that Newcastle was a thriving town with continuous sea-trade with London. There were a number of Dutch immigrants who had settled in Newcastle, including a couple of goldsmiths who, no doubt, would be able to carry out Abraham’s dial engraving.

It is unlikely that the clockmakers already working in Newcastle when Abraham arrived had not heard about the new pendulum clocks, but none except those made by Fromanteel appear to have survived, so we must assume that he was the first longcase clockmaker in the North-east. However by the time he arrived in Newcastle short pendulums with verge (and crown wheel) escapements had been replaced by the anchor escapement and the long (Royal) pendulum in longcase clocks.

It is unlikely that the clockmakers already working in Newcastle when Abraham arrived had not heard about the new pendulum clocks, but none except those made by Fromanteel appear to have survived, so we must assume that he was the first longcase clockmaker in the North-east. However by the time he arrived in Newcastle short pendulums with verge (and crown wheel) escapements had been replaced by the anchor escapement and the long (Royal) pendulum in longcase clocks.

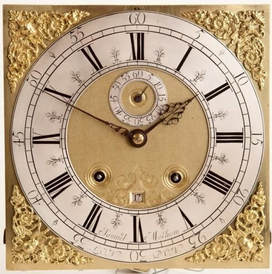

Figure 1: The dial from a 30-hour longcase clock by Abraham Fromanteel

Figure 1: The dial from a 30-hour longcase clock by Abraham Fromanteel

The earliest of Abraham’s longcase clocks to survive is a 30-hour clock which I first described in my book “Clockmakers of Northumberland and Durham”, published in 1980, and which is shown here in figure 1. Although this dial is rather plain it is clear and crisp which, to my mind, makes it a very attractive clock. It has a number of features which indicate its early origins. The spandrels are the earliest design of winged cherub head, which is quite small, and only used on the earlier longcase dials made between 1660 and 1675. Some early dials had no spandrels but the corners were engraved with floral patterns. Later dials have a larger and more ornate winged cherub head spandrel introduced about 1675 and used until about 1710. This dial is 9 ¾ in. wide and the chapter ring is 9 in. wide (outer diameter) and 1 ½ in. deep. Earlier dials were smaller and chapter rings were smaller and shallower (8 in. diameter, 1 in. deep) before 1670, but later dials are larger with 10 in. chapter rings varying in depth (2-2 ½ in.) between 1680 and 1700.

The half-hour markers on this chapter ring are the fleur-de-lis design, used on the early rings but later designs differ from this simple version, and the smallest time interval recorded is a quarter of an hour, with the single hour hand. The hand is quite plain and heavy compared to later designs and is reminiscent of lantern clock hands. The tail of this hand has been removed some time since it was made. The dial centre has been stippled with a very fine punch to give the resulting, rather pleasing, velvet appearance.

The signature on this dial, “A. Fromanteel, Newcastle”, on the bottom edge of the dial-plate (typical of early clocks 1665-1685) is somewhat like a handwritten signature, a cross between writing and printing. Because of the need to ‘import’ chapter rings from London into the provinces, and the shortage of engravers there, signatures appear on provincial chapter rings earlier than they did on some London chapter rings (about 1680).

Probably the most interesting feature of this dial, from an historical point of view, is not readily visible. The dial plate has a punch mark. The number 44, beneath the chapter ring and also on the rear of the chapter ring. This will help us to date the clock later.

The half-hour markers on this chapter ring are the fleur-de-lis design, used on the early rings but later designs differ from this simple version, and the smallest time interval recorded is a quarter of an hour, with the single hour hand. The hand is quite plain and heavy compared to later designs and is reminiscent of lantern clock hands. The tail of this hand has been removed some time since it was made. The dial centre has been stippled with a very fine punch to give the resulting, rather pleasing, velvet appearance.

The signature on this dial, “A. Fromanteel, Newcastle”, on the bottom edge of the dial-plate (typical of early clocks 1665-1685) is somewhat like a handwritten signature, a cross between writing and printing. Because of the need to ‘import’ chapter rings from London into the provinces, and the shortage of engravers there, signatures appear on provincial chapter rings earlier than they did on some London chapter rings (about 1680).

Probably the most interesting feature of this dial, from an historical point of view, is not readily visible. The dial plate has a punch mark. The number 44, beneath the chapter ring and also on the rear of the chapter ring. This will help us to date the clock later.

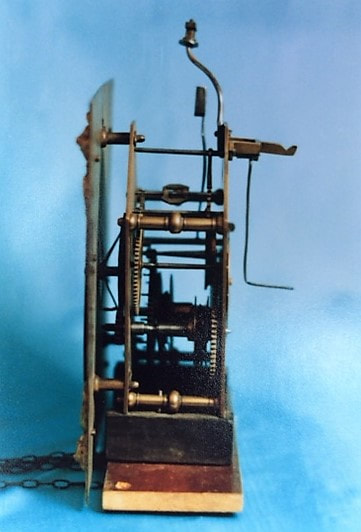

Figure 2: The movement of Abraham Fromanteel's 30-hour longcase flock

Figure 2: The movement of Abraham Fromanteel's 30-hour longcase flock

It has been said that because provincial clockmakers were not influenced by the lantern clock (and did not make them) they did not use post-framed movements in their clocks. However here we have a London-trained clockmaker, working in the provinces, who did make lantern clocks, but who did not use a post-framed movement in his 30-hour clocks.

As we can see in figure 2 Fromanteel’s movement has a plated- frame, the four pillars of which are pinned to the plates, while the dial plate is latched to the movement. On his eight-day movements he used latches to fasten the pillars to the plates. The Fromanteel output after the new pendulum clocks were introduced was obviously mostly new longcase clocks and very few old style lantern clocks, whereas other London makers must have continued to make a number of lantern clocks, otherwise they too would have standardised their output to only plate-framed movements.

Even after 1680 some London clockmakers were using the post-framed movements for their 30-hour clocks. Makers like Richard Colston, who has been recognised as one of the better London clockmakers, was using old style movements in his 30-hour clocks but the new style movements in his 8-day and longer duration clocks. Richard Colston was apprenticed to his father John and not freed until 1682, so should not have been influenced by the lantern clock, unless he was making lantern clocks in large numbers during his apprenticeship.

Perhaps there was another reason for the popularity of the post-framed movement in the southern counties, because clockmakers there continued to use it well into the 18th century. They may have been cheaper to produce than the plated movements.

Returning to the 30-hour movement made by Abraham Fromanteel we can see that the main wheel is quite large in proportion to the plates, as are the centre and escape wheels. The escapement of this clock is particularly interesting as it is an experimental version of the anchor escapement. It has longer pallets than other anchor escapements and shaped like an inverted V, having club feet which span only five teeth of the large escape wheel. Very few of these experimental anchor escapements are found in clocks surviving today. I have seen them only in clocks by the Fromanteels and Joseph Knibb who was thought to have some close ties with the Fromanteels and whose name has been put forward as one of the contenders for the inventor of the anchor escapement.

The anchor escapement was invented before 1670 so it seems likely that Abraham knew about the anchor escapement, which is regulated by the long (or Royal) pendulum, before he moved to Newcastle about 1669.

The fly on this movement is reminiscent of the design used in lantern clocks being long and narrow, whereas later longcase flies were shorter but wider and spreading further across their arbors.

The back plate of this 30-hour movement reveals an inverted heart-shaped hole under the back cock which is for easy removal of the long pallets from the movement. The two top corners of both plates are cut away to allow the bell to be fitted low down over the movement because early case hoods were quite short and close-fitting.

The circular disc on the back plate is the locking-plate (count wheel) strike control. Rack striking was introduced about 1676 but it was only used in repeating clocks until well after 1700, when it was only used in eight-day and longer duration clocks. However locking-plate strike control was used in 30-hour clocks right through the 18th and 19th centuries, presumably because it was cheaper.

As we can see in figure 2 Fromanteel’s movement has a plated- frame, the four pillars of which are pinned to the plates, while the dial plate is latched to the movement. On his eight-day movements he used latches to fasten the pillars to the plates. The Fromanteel output after the new pendulum clocks were introduced was obviously mostly new longcase clocks and very few old style lantern clocks, whereas other London makers must have continued to make a number of lantern clocks, otherwise they too would have standardised their output to only plate-framed movements.

Even after 1680 some London clockmakers were using the post-framed movements for their 30-hour clocks. Makers like Richard Colston, who has been recognised as one of the better London clockmakers, was using old style movements in his 30-hour clocks but the new style movements in his 8-day and longer duration clocks. Richard Colston was apprenticed to his father John and not freed until 1682, so should not have been influenced by the lantern clock, unless he was making lantern clocks in large numbers during his apprenticeship.

Perhaps there was another reason for the popularity of the post-framed movement in the southern counties, because clockmakers there continued to use it well into the 18th century. They may have been cheaper to produce than the plated movements.

Returning to the 30-hour movement made by Abraham Fromanteel we can see that the main wheel is quite large in proportion to the plates, as are the centre and escape wheels. The escapement of this clock is particularly interesting as it is an experimental version of the anchor escapement. It has longer pallets than other anchor escapements and shaped like an inverted V, having club feet which span only five teeth of the large escape wheel. Very few of these experimental anchor escapements are found in clocks surviving today. I have seen them only in clocks by the Fromanteels and Joseph Knibb who was thought to have some close ties with the Fromanteels and whose name has been put forward as one of the contenders for the inventor of the anchor escapement.

The anchor escapement was invented before 1670 so it seems likely that Abraham knew about the anchor escapement, which is regulated by the long (or Royal) pendulum, before he moved to Newcastle about 1669.

The fly on this movement is reminiscent of the design used in lantern clocks being long and narrow, whereas later longcase flies were shorter but wider and spreading further across their arbors.

The back plate of this 30-hour movement reveals an inverted heart-shaped hole under the back cock which is for easy removal of the long pallets from the movement. The two top corners of both plates are cut away to allow the bell to be fitted low down over the movement because early case hoods were quite short and close-fitting.

The circular disc on the back plate is the locking-plate (count wheel) strike control. Rack striking was introduced about 1676 but it was only used in repeating clocks until well after 1700, when it was only used in eight-day and longer duration clocks. However locking-plate strike control was used in 30-hour clocks right through the 18th and 19th centuries, presumably because it was cheaper.

Figure 3: Longcase clock by Abraham Fromanteel

Figure 3: Longcase clock by Abraham Fromanteel

The last photograph (figure 3) shows how this fine clock would have looked in its original case. Although the original case was destroyed because of woodworm attack this attractive reproduction illustrates the high quality which still can be achieved by some modern casemakers.

With the information we have about Abraham Fromanteel we should be able to date this clock fairly precisely. He came to Newcastle about 1669 and returned to London, after the deaths of his wife, Priscilla, in April 1679 and his baby daughter, Mary, in November 1679, to take up his freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1680. He did eventually ‘retire’ to Newcastle about 1711, when he would be 65, but this need not concern us at the moment.

The clock is numbered, 44, so if we could estimate Abraham’s rate of production we can find out when he made it.

We know from the records of one or two clockmakers which have survived and also from the engraving records of the Beilby and Bewick partnership, that it took the average clockmaker about two weeks to make a clock. So we might assume that Fromanteel could produce a maximum of 25 clocks a year. However this does not take into account the number of watches he might finish in a year, or the number of repairs he might undertake. We also have to make allowance for the fact that not many people would know of his presence at first, although news of the new clocks would soon spread in a closely knit community.

An important fact we do know is that Fromanteel must have reached full capacity by 1671 when he took Deodatus Threlkeld as his apprentice.

There are other factors we might consider in our calculation, for example, he may have been receiving parts or even complete clocks from the workshop in London, but this is unlikely due to the delays which might occur between ordering and receiving the goods.

So for argument’s sake, let us say that he made 10 clocks in 1669, 15 clocks in 1670 and 20 clocks in 1671, which would give him a total of 45 clocks in his first three years and number 44 could have been made in late 1671. So if we conclude that it was made between 1670 and 1673 we should not be too far out.

Of course if we could find other numbered clocks by Abraham Fromanteel made in this period, 1669-1680, we would be in a position to calculate his rate of production with greater accuracy.

With the information we have about Abraham Fromanteel we should be able to date this clock fairly precisely. He came to Newcastle about 1669 and returned to London, after the deaths of his wife, Priscilla, in April 1679 and his baby daughter, Mary, in November 1679, to take up his freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1680. He did eventually ‘retire’ to Newcastle about 1711, when he would be 65, but this need not concern us at the moment.

The clock is numbered, 44, so if we could estimate Abraham’s rate of production we can find out when he made it.

We know from the records of one or two clockmakers which have survived and also from the engraving records of the Beilby and Bewick partnership, that it took the average clockmaker about two weeks to make a clock. So we might assume that Fromanteel could produce a maximum of 25 clocks a year. However this does not take into account the number of watches he might finish in a year, or the number of repairs he might undertake. We also have to make allowance for the fact that not many people would know of his presence at first, although news of the new clocks would soon spread in a closely knit community.

An important fact we do know is that Fromanteel must have reached full capacity by 1671 when he took Deodatus Threlkeld as his apprentice.

There are other factors we might consider in our calculation, for example, he may have been receiving parts or even complete clocks from the workshop in London, but this is unlikely due to the delays which might occur between ordering and receiving the goods.

So for argument’s sake, let us say that he made 10 clocks in 1669, 15 clocks in 1670 and 20 clocks in 1671, which would give him a total of 45 clocks in his first three years and number 44 could have been made in late 1671. So if we conclude that it was made between 1670 and 1673 we should not be too far out.

Of course if we could find other numbered clocks by Abraham Fromanteel made in this period, 1669-1680, we would be in a position to calculate his rate of production with greater accuracy.

As it happens an eight-day longcase clock by Fromanteel of Newcastle was described in an article mentioned earlier by Aghib and Leobold. The clock they described had all the Fromanteel characteristics, early type of anchor escapement with the long pallets, heart- shaped hole in the back plate, and cut-away corners on the top pf the plates. The clock had an eight-day movement with bolt-and-shutter maintaining power, inside count wheel strike control and latched plates.

The dial of this clock had a similar chapter ring to the 30-hour clock, i.e. same size and same half-hour markers, but in addition it had a minute band around the outer edge. The spandrels, however, were of a later design, larger and more ornate winged cherub head style used about 1675-1720. Their clock also had a date aperture and subsidiary seconds chapter ring and the hands were finely pierced and nicely finished.

The clock was clearly signed ‘Fromanteel, Newcastle’ at the bottom edge of the dial plate, indicating that their clock was made after Abraham had become established and was simply known as “Fromanteel”. I would date this clock nearer 1680 and made just before his return to London.

The dial of this clock had a similar chapter ring to the 30-hour clock, i.e. same size and same half-hour markers, but in addition it had a minute band around the outer edge. The spandrels, however, were of a later design, larger and more ornate winged cherub head style used about 1675-1720. Their clock also had a date aperture and subsidiary seconds chapter ring and the hands were finely pierced and nicely finished.

The clock was clearly signed ‘Fromanteel, Newcastle’ at the bottom edge of the dial plate, indicating that their clock was made after Abraham had become established and was simply known as “Fromanteel”. I would date this clock nearer 1680 and made just before his return to London.

NOW available for online purchase.

"Thanks for writing your book, I have read all the non-directory sections closely and enjoyed it all. I never fully understood the detail of the South Sea Bubble until now, which is fascinating. The book is a fountain of knowledge and I will always treasure it"

Charles - London

"Thanks for writing your book, I have read all the non-directory sections closely and enjoyed it all. I never fully understood the detail of the South Sea Bubble until now, which is fascinating. The book is a fountain of knowledge and I will always treasure it"

Charles - London

Early Clock and Watchmakers of the Blacksmiths' CompanyKeith's years of research into the Blacksmiths' Company have uncovered the history of many clock and watchmakers. Contains over 400 illustrations and a directory of over 1,500 clock and watchmakers...many previously unknown.

Early Clock and Watchmakers of the Blacksmiths’ Company Now available for purchase for £79 plus FREE P&P (UK delivery) or £30 P&P (EU & USA delivery) |

|

|

|