Early longcases from the North East - Deodatus Threlkeld

By Keith Bates

Article in Clocks Magazine of December 1990.

The trade guilds of Newcastle were dominated for centuries by the Merchant Adventurers Guild which claimed a monopoly of buying and selling of merchandise in the town. The purchase and sale of certain foreign goods was forbidden; a number of freemen were fined and the materials confiscated for SELLING IMPORTED IRON.

The Merchants’ Guild was made up of mercers, drapers and boothmen but other tradesmen, like grocers and spicers, came under the jurisdiction of the guild. In 1672 an apothecary, Richard Bates agreed to pay a fine of £100 (£20,000 TODAY) to be allowed to trade freely and to be accepted as a member of the guild.

The craftsmen of Newcastle had resented the monopoly of the merchants and the disputes reached such a proportion by the beginning of the 16th century that Henry VIII ordered an investigation in 1515. However it was not until 1536 that five goldsmiths joined with the plumbers, glaziers, pewterers and painters to form a separate craft guild. The freemen of this company were all recorded as glaziers until near the end of the 17th century when the separate trades are mentioned but some goldsmiths were still recorded as glaziers even later and it was not until 1716 that they broke away from the parent company.

The Merchants’ Guild was made up of mercers, drapers and boothmen but other tradesmen, like grocers and spicers, came under the jurisdiction of the guild. In 1672 an apothecary, Richard Bates agreed to pay a fine of £100 (£20,000 TODAY) to be allowed to trade freely and to be accepted as a member of the guild.

The craftsmen of Newcastle had resented the monopoly of the merchants and the disputes reached such a proportion by the beginning of the 16th century that Henry VIII ordered an investigation in 1515. However it was not until 1536 that five goldsmiths joined with the plumbers, glaziers, pewterers and painters to form a separate craft guild. The freemen of this company were all recorded as glaziers until near the end of the 17th century when the separate trades are mentioned but some goldsmiths were still recorded as glaziers even later and it was not until 1716 that they broke away from the parent company.

The Blacksmiths' Hall at Blackfriars in Newcastle.

The Blacksmiths' Hall at Blackfriars in Newcastle.

The much older Smiths’ Guild had been formed in 1436 when a number of blacksmiths, whitesmiths and locksmiths had combined to form a trade guild but unfortunately very little information and very few records of the guild have survived. On the other hand their counterparts, the Hammermens’ Guild in Edinburgh, was a company of armourers, cutlers, sadlers, blacksmiths, beltmakers, locksmiths and braziers and is described by James Colson in his book “The Incorporated Trades of Edinburgh, published in 1891.

Apparently the locksmiths of Edinburgh were in a separate branch of the same guild together with the clockmakers (knockmakers). Each member of the company was confined to the practice of his own particular branch of manufacture until 1647, when a person qualified as a locksmith and knockmaker (clockmaker) produced “a lock with key and sprent band and knock with minutes and dyall”. He was admitted with the consent of the locksmiths and clockmakers and was the first to practise the joint trade. The clock with minutes and dial would of course be a turret clock with dial showing the minutes, and striking the hours.

It is interesting to note how the essay or masterpiece is amended from time to time as the work of the clockmaker changed. In 1677 the clockmaker’s essay was altered to “ the movement of a watch” and again in 1689 it was changed to the production of “a house clock with a watch alarum, and locks upon the doors”. It is interesting to find that the house clock made had to be provided with alarm work and locks for the case doors.

Although the above information is interesting in itself it does not exclude the possibility that watchmakers were working independently of the guild before these dates. It is more than likely that they were working in Edinburgh from the beginning of the 17th century as they were in Newcastle and that house clocks were first made by these watchmakers. Abraham Fromanteel would be producing house clocks in Newcastle from about 1670, so it is possible that a London trained watchmaker could have moved to Edinburgh at about the same time or earlier.

Apparently the locksmiths of Edinburgh were in a separate branch of the same guild together with the clockmakers (knockmakers). Each member of the company was confined to the practice of his own particular branch of manufacture until 1647, when a person qualified as a locksmith and knockmaker (clockmaker) produced “a lock with key and sprent band and knock with minutes and dyall”. He was admitted with the consent of the locksmiths and clockmakers and was the first to practise the joint trade. The clock with minutes and dial would of course be a turret clock with dial showing the minutes, and striking the hours.

It is interesting to note how the essay or masterpiece is amended from time to time as the work of the clockmaker changed. In 1677 the clockmaker’s essay was altered to “ the movement of a watch” and again in 1689 it was changed to the production of “a house clock with a watch alarum, and locks upon the doors”. It is interesting to find that the house clock made had to be provided with alarm work and locks for the case doors.

Although the above information is interesting in itself it does not exclude the possibility that watchmakers were working independently of the guild before these dates. It is more than likely that they were working in Edinburgh from the beginning of the 17th century as they were in Newcastle and that house clocks were first made by these watchmakers. Abraham Fromanteel would be producing house clocks in Newcastle from about 1670, so it is possible that a London trained watchmaker could have moved to Edinburgh at about the same time or earlier.

The Blacksmiths' Crest on the hall at Blackfriars.

The Blacksmiths' Crest on the hall at Blackfriars.

It is possible that the locksmiths and clockmakers of Newcastle had a similar guild because in 1607 a locksmith called James Wilson was made a freeman of the Smiths’ Guild but we know from parish records that a clockmaker by the same name was working there by 1619. Also Sopwith in his essay “Account and plan of All Saints Church” records that John Moody worked on the church clock in 1639 and William Moody in 1662. From the list of Freemen we find that in 1646 William Moodie son of John Moodie, locksmith, was given his freedom of the Smiths’ Guild.

Unfortunately the records of the early activities of the Smiths’ Guild of Newcastle have been lost so we may never know what information they contained about early clockmakers in the Town.

However the names of known clockmakers working at the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century do not appear in the lists of freemen of the various companies so we must assume that the majority at least were not affiliated to any guild. Without guild records we have no definite proof of apprenticeship bindings; when and to whom an apprentice was bound and lists of freemen to give dates from which a clockmaker could be working for himself.

Unfortunately the records of the early activities of the Smiths’ Guild of Newcastle have been lost so we may never know what information they contained about early clockmakers in the Town.

However the names of known clockmakers working at the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century do not appear in the lists of freemen of the various companies so we must assume that the majority at least were not affiliated to any guild. Without guild records we have no definite proof of apprenticeship bindings; when and to whom an apprentice was bound and lists of freemen to give dates from which a clockmaker could be working for himself.

We are fortunate in the case of Deodatus Threlkeld in being able to deduce who his Master was. There was only one London trained clockmaker working in Newcastle in 1671, when Threlkeld was apprenticed, who could have shown him how to make clocks of such excellent quality, Abraham Fromanteel. Not only do Threlkeld’s clocks show London features (latched pillars) but they also have Fromanteel’s characteristics; the top corners of the movement plates are cut away on some of his clocks, as illustrated in my Fromanteel article in the October issue of ‘Clocks’.

Most apprentices in the 17th century served at least seven years with a clockmaker before they were released, while a number stayed on a further two years as journeymen before setting up a business on their own.

Threlkeld would be free in 1678 and probably stayed on with Fromanteel as a journeyman until the latter returned to London in 1680. By 1684 Threlkeld was well established in business and a respected member of the community when he married Hannah Anderson, daughter of a landowner from Newburn. Before her death in 1697 Hannah had borne him several children, only two of whom survived to adulthood, Deodatus, junior, born in 1687 and Hannah born in 1689.

Threlkeld then married Margaret, daughter of landowner, George Ilderton of Ilderton, on 3rd January 1698/9. Unfortunately she died in childbirth later the same year, and Threlkeld was granted administration of her estate in October 1699.

Threlkeld then married Margaret Moor of Whickham on 29th October 1700, and they had three surviving children: John, born September 1701; Thomas, born September 1707 and Elizabeth, born November 1712.

Deodatus II was apprenticed to his father from 1701 to 1708 but as soon as he was released he must have left the business and signed himself over to Thomas Brown, a master mariner, as he was given his freedom of the Mariners’ Company in 1715. He left Newcastle never to return, but married in Burmuda and eventually settled in Virginia, USA . He also had a son Deodatus, but it is not known if either father or son worked as a watchmaker there.

Threlkeld’s son John was apprenticed to his godfather, John Bowes, draper and Sheriff of Newcastle on 17th August 1717 and was turned over to William Leighton on 18th May 1718, after the death of John Bowes, and was admitted free of the Merchant Adventurers Guild on 2nd May 1728. John set up in business on his own account on 2 April 1729 with the financial backing of his father.

In November 1731 John married Jane, daughter of Gawen Aynsley of Harnham, against the wishes of both families with the result that his father, Deodatus, withdrew his financial backing and John was declared bankrupt. However through the parliamentary influence of Sir William Middleton of Belsay John was appointed postmaster for the town of Morpeth.

Third son Thomas was apprenticed in 1723 to Thomas Hunter, a mercer, and was turned over to Cuthbert Smith in September 1724 and admitted a freeman of the Merchant Adventurers Guild in October 1733.

Apart from Deodatus II it has only been possible, so far, to identify only two of Threlkeld’s other apprentices. The first was Robert Ilderton, 1680-1687, son of George Ilderton and elder brother of Margaret, Threlkeld’s second wife. Ilderton set up on his own in Alnwick after gaining his freedom but moved back to Newcastle about 1708, where he lived and worked as a gentleman watchmaker until he retired about 1730.

The second was Threlkeld’s nephew William Threlkeld, son of his eldest brother Henry, skinner and glover of Brancepath. William, apprenticed from 1688 to 1695, worked as a journeyman for Deodatus until 1697 when he left for London with Martin Jackson of Brancepath, another locally trained watchmaker. William did not join the Clockmakers’ Company, although he was working on his own account in the Strand by 1700, but Jackson did join the Company. William did eventually retired to Brancepath about 1740.

Having developed a successful business and established himself as a leading member of the community Threlkeld ‘retired’ in 1723 to his country estate at Tritlington, near Morpeth, where he continued to make and repair watches. When he died in February 1732/3 he left his son John £20 per annum, but the major part of his estate was left to his youngest son Thomas, while his eldest son Deodatus II was not even mentioned in the will.

Threlkeld’s success was not just due to his skill as a craftsman, but also to his shrewd business brain and his guile at outwitting his competitors. Early competition from John Davis, 1686, George Carter, 1686 and John Nelson, 1686, seems to have been short-lived, while William Shaftoe, 1664-1689, and William Shawter, 1678-1690, both managed to compete for a time but eventually moved elsewhere. However Henry Emmerson, 1685- 1705d, managed to survive in business alongside Threlkeld until his death in 1705.

By far the biggest threat to Threlkeld’s supremacy came about the same time, between 1685 and 1700, from one who appeared to be a London trained clockmaker, William Prevost, whose clocks we will examine in my next article, when I will expain how he was outmanoeuvred by Threlkeld.

Even though Threlkeld’s work was held in high regard during his lifetime very few of his clocks remain today. However those which have survived the ravages of time and human destruction give us an insight into the skill and application of a true craftsman. There are about eight longcase clocks, two of which have month movements, two or three table (bracket) clocks and a few watches for us to judge 43 years of achievement.

Among his longcase clocks, which span the whole of the 43 years, are a wide variety of cases, from beautiful marquetry ones in light and dark veneers, plain walnut, plain oak, and ebonised pine cases.

My favourite one is a fine month duration clock in a plain pine case which was originally ebonised but is now stripped. This clock was made about 1690 when Threlkeld was at the peak of his career, and demonstrates his exceptional skill as a craftsman. The dial and movement of this clock display a quality seldom found outside London.

Most apprentices in the 17th century served at least seven years with a clockmaker before they were released, while a number stayed on a further two years as journeymen before setting up a business on their own.

Threlkeld would be free in 1678 and probably stayed on with Fromanteel as a journeyman until the latter returned to London in 1680. By 1684 Threlkeld was well established in business and a respected member of the community when he married Hannah Anderson, daughter of a landowner from Newburn. Before her death in 1697 Hannah had borne him several children, only two of whom survived to adulthood, Deodatus, junior, born in 1687 and Hannah born in 1689.

Threlkeld then married Margaret, daughter of landowner, George Ilderton of Ilderton, on 3rd January 1698/9. Unfortunately she died in childbirth later the same year, and Threlkeld was granted administration of her estate in October 1699.

Threlkeld then married Margaret Moor of Whickham on 29th October 1700, and they had three surviving children: John, born September 1701; Thomas, born September 1707 and Elizabeth, born November 1712.

Deodatus II was apprenticed to his father from 1701 to 1708 but as soon as he was released he must have left the business and signed himself over to Thomas Brown, a master mariner, as he was given his freedom of the Mariners’ Company in 1715. He left Newcastle never to return, but married in Burmuda and eventually settled in Virginia, USA . He also had a son Deodatus, but it is not known if either father or son worked as a watchmaker there.

Threlkeld’s son John was apprenticed to his godfather, John Bowes, draper and Sheriff of Newcastle on 17th August 1717 and was turned over to William Leighton on 18th May 1718, after the death of John Bowes, and was admitted free of the Merchant Adventurers Guild on 2nd May 1728. John set up in business on his own account on 2 April 1729 with the financial backing of his father.

In November 1731 John married Jane, daughter of Gawen Aynsley of Harnham, against the wishes of both families with the result that his father, Deodatus, withdrew his financial backing and John was declared bankrupt. However through the parliamentary influence of Sir William Middleton of Belsay John was appointed postmaster for the town of Morpeth.

Third son Thomas was apprenticed in 1723 to Thomas Hunter, a mercer, and was turned over to Cuthbert Smith in September 1724 and admitted a freeman of the Merchant Adventurers Guild in October 1733.

Apart from Deodatus II it has only been possible, so far, to identify only two of Threlkeld’s other apprentices. The first was Robert Ilderton, 1680-1687, son of George Ilderton and elder brother of Margaret, Threlkeld’s second wife. Ilderton set up on his own in Alnwick after gaining his freedom but moved back to Newcastle about 1708, where he lived and worked as a gentleman watchmaker until he retired about 1730.

The second was Threlkeld’s nephew William Threlkeld, son of his eldest brother Henry, skinner and glover of Brancepath. William, apprenticed from 1688 to 1695, worked as a journeyman for Deodatus until 1697 when he left for London with Martin Jackson of Brancepath, another locally trained watchmaker. William did not join the Clockmakers’ Company, although he was working on his own account in the Strand by 1700, but Jackson did join the Company. William did eventually retired to Brancepath about 1740.

Having developed a successful business and established himself as a leading member of the community Threlkeld ‘retired’ in 1723 to his country estate at Tritlington, near Morpeth, where he continued to make and repair watches. When he died in February 1732/3 he left his son John £20 per annum, but the major part of his estate was left to his youngest son Thomas, while his eldest son Deodatus II was not even mentioned in the will.

Threlkeld’s success was not just due to his skill as a craftsman, but also to his shrewd business brain and his guile at outwitting his competitors. Early competition from John Davis, 1686, George Carter, 1686 and John Nelson, 1686, seems to have been short-lived, while William Shaftoe, 1664-1689, and William Shawter, 1678-1690, both managed to compete for a time but eventually moved elsewhere. However Henry Emmerson, 1685- 1705d, managed to survive in business alongside Threlkeld until his death in 1705.

By far the biggest threat to Threlkeld’s supremacy came about the same time, between 1685 and 1700, from one who appeared to be a London trained clockmaker, William Prevost, whose clocks we will examine in my next article, when I will expain how he was outmanoeuvred by Threlkeld.

Even though Threlkeld’s work was held in high regard during his lifetime very few of his clocks remain today. However those which have survived the ravages of time and human destruction give us an insight into the skill and application of a true craftsman. There are about eight longcase clocks, two of which have month movements, two or three table (bracket) clocks and a few watches for us to judge 43 years of achievement.

Among his longcase clocks, which span the whole of the 43 years, are a wide variety of cases, from beautiful marquetry ones in light and dark veneers, plain walnut, plain oak, and ebonised pine cases.

My favourite one is a fine month duration clock in a plain pine case which was originally ebonised but is now stripped. This clock was made about 1690 when Threlkeld was at the peak of his career, and demonstrates his exceptional skill as a craftsman. The dial and movement of this clock display a quality seldom found outside London.

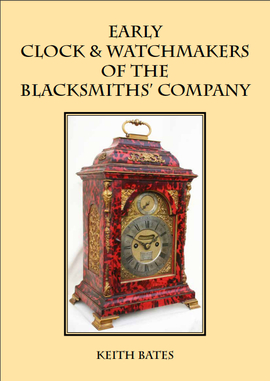

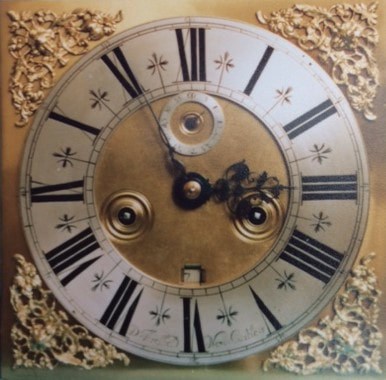

Figure 1: Dial of a Threlkeld clock made around 1690

Figure 1: Dial of a Threlkeld clock made around 1690

The spandrels on this dial (figure 1) are the winged cherub design which as we have already seen were used from 1680 until almost 1720, and the same as those used on the Nelson clock, but with a better finish.

The chapter ring on Threlkeld’s clock looks quite deep, but it is the same size as the Nelson one, 10in in diameter and 2 ¼ in deep.

However the half-hour markers are different; they are the arrowhead design which was introduced about 1690 and used on a number of chapter rings after this date. We can also note that the minute numbering band has been separated from the minute markers, but at this time still quite shallow, growing deeper as the century draws to a close and increasing in size well into the 18th century.

As I mentioned in an earlier article, Abraham Fromanteel’s 30-hour clock was numbered under the chapter ring, so I was anxious to see if Threlkeld also numbered his clocks in the same place. However when I removed the chapter ring I was disappointed to find no number at all, but instead I found what I took to be a brassfounder’s mark on the back of the chapter ring, in the form of an anchor, very like the anchor mark found on later Chelsea china. I wonder if anyone else has come across this mark on chapter rings ?

Another new feature on this dial is the introduction of turned rings around the winding squares, which is found on some clocks made between 1690 and 1730. The date aperture is cut away in a manner which seems unique to Threlkeld’s clocks; at least I have not seen it on any other clockmaker’s dials.

The chapter ring on Threlkeld’s clock looks quite deep, but it is the same size as the Nelson one, 10in in diameter and 2 ¼ in deep.

However the half-hour markers are different; they are the arrowhead design which was introduced about 1690 and used on a number of chapter rings after this date. We can also note that the minute numbering band has been separated from the minute markers, but at this time still quite shallow, growing deeper as the century draws to a close and increasing in size well into the 18th century.

As I mentioned in an earlier article, Abraham Fromanteel’s 30-hour clock was numbered under the chapter ring, so I was anxious to see if Threlkeld also numbered his clocks in the same place. However when I removed the chapter ring I was disappointed to find no number at all, but instead I found what I took to be a brassfounder’s mark on the back of the chapter ring, in the form of an anchor, very like the anchor mark found on later Chelsea china. I wonder if anyone else has come across this mark on chapter rings ?

Another new feature on this dial is the introduction of turned rings around the winding squares, which is found on some clocks made between 1690 and 1730. The date aperture is cut away in a manner which seems unique to Threlkeld’s clocks; at least I have not seen it on any other clockmaker’s dials.

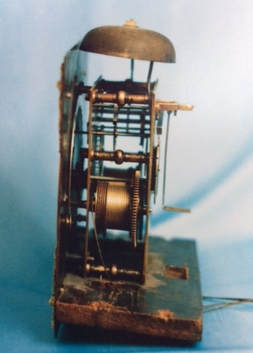

Figure 2: Movement of month going longcase clock by Deodatus Thelkeld

Figure 2: Movement of month going longcase clock by Deodatus Thelkeld

The hands on this month clock are very well finished; the hour hand is nicely pierced but not too ornate, while the minute hand is finely tapered rather like a rapier, its cross section is almost lozenge shaped. The overall finish of this dial is much better than that of the Nelson dial described in my previous article.

The movement of this month clock, (figure 2), measuring 7 ½ in by 5 in, has thinner plates and finer wheelwork than the Nelson clock. It has six nicely turned, ringed pillars which are latched, like London clocks of the same period. The anchor escapement is driven by a five wheel train, like the Nelson clock, and powered by a 24lb weight. Also the striking train is controlled by a rear mounted locking-plate (count wheel).

The movement of this month clock, (figure 2), measuring 7 ½ in by 5 in, has thinner plates and finer wheelwork than the Nelson clock. It has six nicely turned, ringed pillars which are latched, like London clocks of the same period. The anchor escapement is driven by a five wheel train, like the Nelson clock, and powered by a 24lb weight. Also the striking train is controlled by a rear mounted locking-plate (count wheel).

Figure 3: Month going loncase clock by Deodatus Threlkeld..

Figure 3: Month going loncase clock by Deodatus Threlkeld..

The case of this splendid month going longcase clock, (figure 3), is a 6ft 10in pine one, in London style, and has been stripped but would have originally been ebonised. The hood has three quarter wooden pillars, part of the door frame, and painted capitals (not brass ones as most London cases would have) and side windows for observing the movement without removing the hood. The case moulding below the hood is convex, while later clocks, after about 1710, would have a concave moulding. This case, which could well have had a caddy top, is taller and wider than Threlkeld’s eight-day cases to take the heavier weights needed to drive this clock.

Most of Threlkeld’s other surviving clocks are eight-day ones in nicer cases than this one but for some reason this clock was given a cheaper ebonised pine case. Perhaps the original owner preferred to spend more on a better clock than spend extra on a fancy case. Marquetry cases were coming into fashion while ebonised ones were going out of fashion by 1690.

Whatever the reason for housing this outstanding clock in an ordinary case I consider it the work of a true master craftsman and the present owner would not swap this month going Threlkeld clock for all the Ts in Thomas Tompion.

Most of Threlkeld’s other surviving clocks are eight-day ones in nicer cases than this one but for some reason this clock was given a cheaper ebonised pine case. Perhaps the original owner preferred to spend more on a better clock than spend extra on a fancy case. Marquetry cases were coming into fashion while ebonised ones were going out of fashion by 1690.

Whatever the reason for housing this outstanding clock in an ordinary case I consider it the work of a true master craftsman and the present owner would not swap this month going Threlkeld clock for all the Ts in Thomas Tompion.

NOW available for online purchase.

"Thanks for writing your book, I have read all the non-directory sections closely and enjoyed it all. I never fully understood the detail of the South Sea Bubble until now, which is fascinating. The book is a fountain of knowledge and I will always treasure it"

Charles - London

Early Clock and Watchmakers of the Blacksmiths' CompanyKeith's years of research into the Blacksmiths' Company have uncovered the history of many clock and watchmakers. Contains over 400 illustrations and a directory of over 1,500 clock and watchmakers...many previously unknown.

Early Clock and Watchmakers of the Blacksmiths’ Company Now available for purchase for £79 plus FREE P&P (UK delivery) or £30 P&P (EU & USA delivery) |

|

|

|